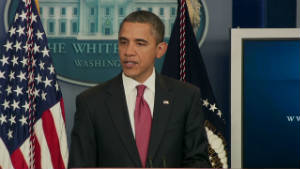

President Barack Obama rolled out his 2012 campaign theme the other day, a populist message with the tired mantra of Republicans as the party of the wealthy while casting himself as the defender of the middle class. “This is a make-or-break moment for the middle class,” he declared. The problem is that, as usual, his record doesn’t match his rhetoric.

A make-or-break moment for the middle class “and all those who are fighting to get into the middle class” would cry out for immediate decisive action to protect that cherished status and give a boost to all those knocking on the door of the American dream.

But that’s not the case when it comes to good-paying energy jobs.

For example, Obama decided to put off for a year construction of the Keystone pipeline to deliver oil from Canada to U.S. refineries on the Gulf Coast. That $7 billion shovel-ready construction project would generate 20,000 jobs. It’s make-or-break time but, hey, job-seekers can wait a year for a chance at an oil pipeline paycheck.

The administration is keeping the lid on oil and gas exploration since the BP oil rig accident, not only preventing new job growth but threatening more job loss. A study of oil permitting by Greater New Orleans Inc. shows that 52 percent of drilling plans in the Gulf of Mexico have been approved this year, down from the historic rate of 73.4 percent. The regulatory maze facing fossil fuels pushed the average approval time to 118 days, nearly twice the historic average of 61 days.

Saying the administration has lifted the BP-inspired moratorium “only in name,” Gregory Rusovich, chairman of the Business Council of Greater New Orleans, declared, “The governmental work stoppage has gone on long enough. Now is the time for action to prevent further job loss.”

“Now is the time for action” echoes the sentiment of Obama’s speech. But his political desire to score points with environmentalists and to promote unprofitable green energy schemes trumps this “make-or-break moment.”

The president uses his rhetoric to push his latest “jobs” plan, a one-year extension of a temporary payroll tax cut to be funded by a tax hike on the rich. There’s little evidence this temporary measure has helped the economy much.

A make-or-break moment calls for fundamental reform — like the economic blueprint presented by Obama’s deficit reduction commission a year ago. It got the cold shoulder from Obama. Its concept of raising more revenues for the government through a simpler tax code with lower rates and few or no deductions runs afoul of Obama’s populist rabble rousing over raising taxes for the rich.

Closing loopholes would also deliver a blow to crony capitalism in Washington and the influence of lobbyists. It would deprive Washington of avenues to pick winners and losers in the economy, a reduction in political clout that Obama and other big-government advocates cannot abide.

Obama mocked common-sense Republican assertions that the economy needs breathing room from red tape. Yet the huge expansion of government rule-making on his watch — the Dodd-Frank finance bill — failed to stop the finagling of Jon Corzine, the former Democratic New Jersey governor for whom Obama campaigned. Corzine’s financial machinations plunged MF Global into the eighth-largest bankruptcy in U.S. history with $1.2 billion in customer money missing.

A “make-or-break moment” requires more than words; it demands commitment and action.